Hash tables are one of the most commonly discussed data structures in Computer Science. Hash tables, in short are used to identify a particular object from a set of similar objects.

They are more efficient than other data structures used for searching, like trees and other tabular searching structures.

Note that all of the books can be represented easily in each of the shelves. But suppose you wanted to identify each of the books without having to search too much. Suppose you wanted to identify each of the books automatically with just the title, i.e., identify the book at O(1) efficiency.

We can evenly divide the books into two or three groups as shown here, but this does not improve the efficiency of the search. The way to do this is to run a computer program that will automatically give you an identity for each book. This identity is the same identity for the book every time you look up the title. For convenience, let us suppose the rows of the bookshelf are lined with numbers and the columns are lined with alphabets, like in Excel.

This computer program gives you the shelf number (row number) and the slot number (column number). This is called a hash algorithm. The key, in this example is the title of the book. So essentially, you pass the title through the hash function and it spits out some value, which is where you would place the book. Suppose the hash function is the sum of the alpha values of the first word of the title that isn't 'a' or 'the' or 'an', using the scale a=1, b=2, c=3..., z=26.

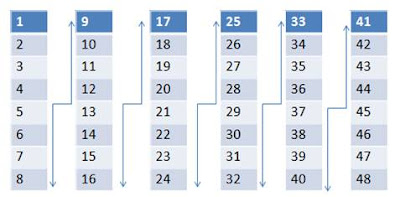

We can notice some obvious problems here, but first, let's make sure we have our understanding of the visual hash table function and book example correct (Note: The diagram below is supposed to be linear, and the lines are connecting 8 to 9, 16 to 17, 24 to 25, 32 to 33, and 40 to 41).

|

| This is what the hash table looks like properly |

But alas, 48 titles are bound to have some sums that are very repetitive and some titles that aren't used at all. So what would we do with titles that sum up to the same number? This is called a collision. Speaking in terms of a bookshelf, we could place the title next to the title with the same sum. Then, in some cases, there would be more than 1 book per slot, and in some cases 0 books per slot.

Now suppose we title sums that exceed the number 48. Suppose we have a title sum that is 126. In this case, we would calculate the modulo, to see where the number lands when it wraps around the hash table :

This should give you an intuitive idea of what a hash table does.

Next will be an intuitive understanding of the design of a hash table and an implementation of a hash table in C.